History of Sumi-e

The philosophical basis of Sumi-e

To introduce Sumi-e (black ink painting), it is necessary to briefly outline the importance of painting in China, because it is there that the cultural, philosophic and artistic context of monochrome painting originated.

Of all arts in China, painting is the most important one and to a Chinese person, it unveils the mystery of the universe.

It is based on a fundamental philosophy, Taoism, which blends precise concepts of cosmology, human destiny and the relationship between man and the universe.

Painting is the application of this philosophy since it penetrates the mysteries of the universe. One can say that this kind of painting, rather than showing the “wonders of nature”, participates in “nature’s gestures”.

It is a particular “way of life”, a “psychic place” where the true life can be lived and also where art and art of living come together. A sublime work of art tries to create a vital microcosm which reflects the macrocosm. It is sublime because its beauty connects Life to its original Spirit.

In this regard an old saying affirms that “those who are immersed in painting will live longer because life created by the touch of the brush strengthens life itself”.

According to ancient Chinese tradition, the harmony of a work of art reflects the universal harmony of the Tao, which is the supreme and inconceivable principle that has generated the world and rules the secret rhythm of nature.

It is not by chance that the dominant feature of great Chinese painting is landscape, which is always both subtly realistic and metaphorical at the same time.

Human figures and man-made things never avert your eyes from a painting’s focal elements, such as a mountain, a waterfall, a tree, bamboo or an orchid. In fact, their position establishes a climate of symbolic correspondence and by analogy, refers to balances established by the Tao between Heaven and Earth, man and nature, gravity and lightness, fullness and emptiness.

Whether in a living being or in any human creation, “Ki” circulates in all things. It is a spirit, a breath and an intangible force. It is a concept which may appear vague and annoyingly metaphysical to Western sensibility. However, the ideograph of Tao means “The Way”, and a way is made to be taken and followed.

The same principles are embodied by the painter, who through the art of the brush, pushes themselves towards Life and allows Life to manifest itself through their works of art, since “the pressure of the brush should conform to the concept dwelling in the heart” and also “before learning to paint, you first have to learn to calm down your heart in order to make your understanding clearer. You must feel sure that you have learned what you need to know, and that your heart and your hand are in perfect harmony”.

Yet another aphorism by Chag Tsao of Tang era states:

“in the outer world take Creation as a model,

in the inner world, follow the source of your soul”.

Main themes

Nothing reflects the history of the Chinese soul better than painting. The painter in China was not only an artist by profession, but also a philosopher, a wise person. For this reason the Chinese considered painting as “perfect knowledge”, as well as the expression of moral integrity and the cultural level of the painter.

There are four main subjects in the traditional Chinese painting, which are fundamentally the same in Japanese painting: landscapes, portraits, birds and animals, and flowers and trees. As previously stated, in painting, nature often has a symbolic meaning.

For example, bamboo stands for everlasting friendship and longevity. Bamboo represents flexibility rooted in strength. It recalls a flexible inner attitude that strengthens the person, who like the bamboo, facing life’s events, does not fight against change, but rather, flows with it and adapts to it.

The person who behaves in this way is “evergreen”, they remain aware of them self and balanced even when the seasons and phases of life are changing.

The orchid, bamboo, plum tree and chrysanthemum represent the “Ki” or the vital energy of the four seasons and of the four ages of man and are considered the “Four Gentlemen”.

The discussion regarding the subjects to be studied specifically in sumi–e will be addressed later. They represent real models to be imitated or copied in order to learn the technique and the infinite variety of forms in nature.

Historical facts: Introduction and spreading of sumi-e in Japan

In the Kamakura era (1192–1333), when the power of the nobility was taken over by warriors (samurai), the pilgrimages of Zen monks to China and their trading there allowed many Chinese paintings and artefacts to be brought back to Japan.This greatly influenced artists who were working in the temples where the works had been commissioned by patrons and collectors of art (shoguns).

These imports not only inspired change in the subjects of painting, but also fostered an innovative use of colour: the Yamato–e (painting on long scrolls, 9th and 10th centuries) were replaced by the Chinese monochrome technique.

Stemming from the work of the great Chan Buddhist masters and painters of the Tang and Song dynasties, painting with black China ink was characterised in Japan by the diffusion of Suiboku–ga or Sumi–e (end of 13th century).

This painting style was initially monopolised by Zen Buddhists and then adopted by monks and artists imbued with this spirit, and for a long time, painting with black ink (Sumi–e) and Zen painting (Zenga) were practically inseparable.

The greatest sumi–e master of this period is Sesshu (1420–1507), a Zen monk from Kyoto, who studied ink-painting in China with the Chan monk Shubun. Sesshu was the only painter who assimilated the philosophical basis of this kind of painting, and who rendered it with original spirit into Japanese themes and artistic language, also with respect to spatial concepts of Chinese artists of the period.

In China and Japan, the art of painting was traditionally identified with Zen practice. To fully comprehend its peculiarities, it is necessary to understand the philosophical underpinnings of Zen, and the practice of Zen, which is based on the concept of the void as man’s original nature.

A practice based on Emptiness

To express the inexpressible, to communicate what is not possible to communicate, was the seemingly paradoxical intent of Shakyamuni Buddha when, during an assembly at Vulture’s Peak, having been asked to deliver a speech on the Law (the Eternity), he just held a flower in his hand, lifted it and turned it over in his fingers while remaining silent.

Assuming that this was the real intention of the Buddha, we can imagine why, according to this legendary tale, no one of the numerous people present was able to grasp the deep meaning of the Master’s gesture. As with all other things and events in the universe, this did not and could not mean anything at all, therefore, it meant absolutely everything.

Nobody was able to understand, and nobody spoke. Only Mahakashyapa the Great, meeting Buddha’s glance, had a clear disclosure of that boundless Nothing, and, intimately, smiled. Because of that smile, he was considered the keeper of the special message of Buddha and of all his teaching.

This is the ancient heart of Zen, the authentic and immediate expression of the supreme experience of Awakening, that is a dazzling vision of one’s true nature (Satori). From this emptiness one is able to awaken from the great sleep of pain and anguish of human existence.

This inexpressible experience that leads to nirvana (true wisdom where the pain of consciousness ends), Zen practice ’needs to be transmitted directly, “heart to heart”, and is not dependent on words, but rather discovered by looking into one’s own nature, as taught by its legendary founder, Bodhidharma and with the sincere conviction that “if you do not find it in yourself, where else will you find it?”

Those paintings which are considered today as authentic valuable creations, are “direct indications” of that inexpressible nature of the Void, which was discovered by Buddha and which illuminated his prized student’s face.

The Way of the Brush

Zen painting (in particular, the more recently, during the 18th and 19th centuries) is different from painting as commonly understood by western culture.

In fact, Zen paintings, are a type of sketch done in black and white, where white (the paper), represents the universe and black (the ink), represents material forms which ceaselessly appear and disappear within it. To visually express the vital essence of these forms and the eternal meaning that is hidden within them, is the task that is undertaken by a true Zen painting master.

In the tea ceremony we speak of “The Way of Tea”, likewise, painting also can be considered a Way (Do, in Japanese). This is a traditional method of practice valuable for training of your consciousness.

By skilful handling of the brush, you overcome the limits of your own ego and sense of self in order to become attuned with your unconscious self in a “non-conscious state of being”.

Shen Tsung Ch’ien says:

The game of the brush must be dominated by the Breath.

When the Breath is, the vital energy is, it is then that the brush generates the Divine.

However, to correctly practice the Way, requires learning the knowledge on which it is based. Mere techniques are not enough to create a work in Zen style: the artist has to “forget themselves”, and everything that they have previously learned, and find inspiration to become one with their technical skill.

Then “mind and body disappear”, the person and the Being that underlies them become One, and the work of art comes emerges itself, freely and not dependent on the artist’s will. The artist simply follows the natural creation process, without any intentional effort.

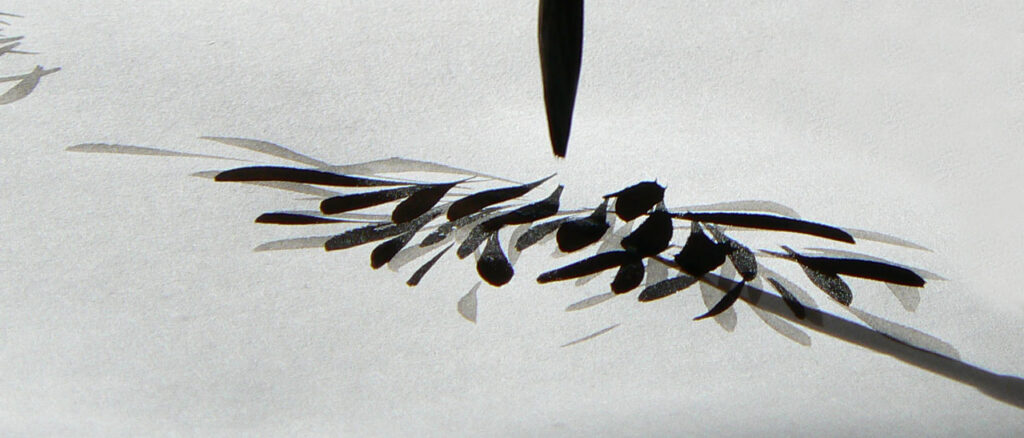

Let’s see for example what happens when we want to paint bamboo with the sumi-e method: you sit down (but you can also stand) with your back straight, you put a sheet of paper in front of you and concentrate on it, breathing calmly and naturally.

You let all other thoughts fade until only a white sheet of paper remains in your mind. Next, you let the image to be painted appear in your mind. In order to paint the bamboo, you must feel its “consistency”, see its stem, its branches, feel its light leaves stirred by a breeze wind or wet, heavy with rain.

Your spirit is full of this and more; it becomes the bamboo, it is indescribable. Then you pick up the brush and let your hand move in a natural way, effortlessly. There is no thought about technique or about the result, there is no conscious effort to make a nice painting. Little by little, your complete bamboo will take shape and you will have a painting that is unquestionably alive. The bamboo is “created” from nothing, not just copied.

On rice paper, only one brush stroke is allowed for each mark: any touch-ups are immediately evident. All mental activities that are complicating the image (and your life) are given-up. So you understand that your thoughts about life, are not life itself and your thoughts about Zen, are not Zen; they are just thoughts.

Master Sung Tung Po says:

Before painting a bamboo, it is necessary for the bamboo to grow in your soul.

Then, with brush in hand and with eyes focused, the vision will arise.

Capture it immediately and sketch it, because it may quickly disappear like a wild rabbit when a hunter is approaching.

The real sumi-e

As previously mentioned, the Japanese term “sumi” means “black ink” and “e” means “painting”. It indicates one of the art forms in which subjects are painted with black ink in all possible gradations ranging from pure black to the lightest shades achieved by diluting the ink with water.

However, this does not mean that everything painted in this way deserves to be called sumi-e.

Real sumi-e must correspond to typical features, such as simplicity and spontaneity that directly strike the viewers’ sensibilities.

In order for a painting to be “alive”, all its components must be alive. This type of painting already includes the sketch; there is no need for preparation. As in traditional painting; any superfluous form or detail is left out.

Sumi-e grasps the essence of nature. It is in tune with the “rhythmic movement of the Spirit” which is present in all things, and which the artist conveys in their painting.

This way of painting was introduced into Japan by Zen monks and it then became rapidly successful because in this painting method, as in Zen practice, reality is expressed by reducing it to its pure, bare form.

Touch-ups, additions and decorations do not enhance a work, but rather hide its true nature. Just as in cooking, if you add too many spices, you won’t get the real flavour of what you have made.

Just as in Zen, few words are enough to express the meaning of many hours of meditation, in sumi-e, few marks of black ink painted with a brush on a simple sheet of white paper, can represent the most complex model. One must learn to capture the essence in order to get to the heart of reality as it is.

How to learn

This way of painting is complete, it involves your whole body. It is not easy at all and working with an expert teacher is necessary, as well as getting used to repeating subjects, or parts of them, innumerable times. The spirit becomes more and more refined and sensitive through constant repetition.

At the start, it is inevitable that your paintings will be cold and unnatural. Eventually, you may wish to have more beauty in your work, although this shouldn’t turn into an obsession of wanting to become a perfect practitioner of sumi-e, since then, by doing so, you wouldn’t make any progress. If you go on thinking in terms of good and bad, you are still far from the true spirit of sumi-e.

As in Zen, the spirit must be free from any voluntary desire for success and ambition. Probably, much sooner than you think, you will feel able to paint whatever you wish, because every part of a landscape will appear as the true reflection of the source of life and nature.

You will also realise that you are breathing better, that your body posture is more upright and “nobler” and that your overall health has also improved, including your spiritual psychological equilibrium.

In Zen, zazen is not just about learning a “meditation technique” but rather, it is about establishing a direct contact with the origin of everything (“Buddha nature”). In the same way, sumi-e goes far beyond a simple “painting technique”.